By Augustus Caesar Esmeralda and Walter Panganiban

The world we live in is volatile, uncertain, complex, and ambiguous — changes happen rapidly; many things are unpredictable; everything is interconnected, and interpretations are subjective. Under this reality, we find ourselves and the systems we have created, constantly at risk. And with the expanding impact of climate change, the risks are growing bigger.

Over the past two decades, we have seen natural and man-made hazards become more severe and occur more frequently. Unfortunately, while our exposure and sensitivity to these hazards have increased, our adaptive capacity has not improved as much. These are the challenges of building disaster resilience — reducing our exposure and sensitivity and increasing our ability to adjust to potential disasters.

But before we even attempt to build resilience, we need to understand what it is first.

Resilience = Robustness + Flexibility + Agility

Any online search on the definition of resilience will reveal many entries.

- a system property which denotes the degree of shock or change that can be tolerated while the system maintains its structure, basic functioning, and organization (Defining Resilience, Adaptive Capacity, and Vulnerability, 2018))

- a process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats or significant sources of stress (Building Your Resilience, 2012)

- the capability of a strained body to recover its size and shape after deformation caused especially by compressive stress (Resilience, n.d.)

- the ability to recover from or adjust easily to misfortune or change (Resilience, n.d.)

Using the four definitions listed here, we come to a general understanding of resilience as the ability to bounce back or recover from any disruption or shock. Notice, however, the definitions referenced different aspects or elements of resilience.

For a system to recover, it would require, to some degree, the ability to withstand shocks — robustness, the ability to adjust to changes — flexibility, or the ability to respond immediately to unplanned developments — agility. If none of its parts remains intact, adjust to the impact, or address the shock in a way that allows it to survive, a system will not recover.

This runs parallel to the definition of resilience espoused by the United Nations Office of Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), formerly known as the UN International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR).

Resilience means the ability of the system, community, or society exposed to hazards to resist, absorb, accommodate, adapt to, and recover from the effects of the hazard in a timely and efficient manner including through the preservation and restoration of its essential basic structures and functions (UNISDR, 2009)

Resilience = Bounce Back Better

But recovering from a shock or a disaster is not enough. Systems need to recover better and faster. Hence, this paper stands on the position that being resilient means being able to bounce back better.

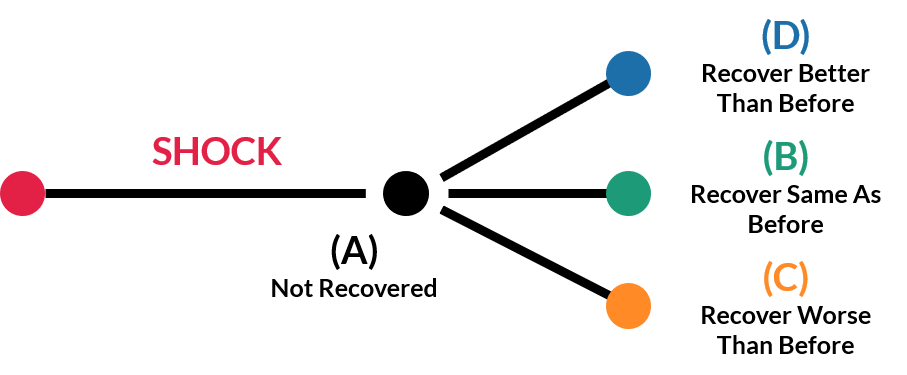

Remember that there are four potential outcomes from any shock.

- The system does not recover.

- The system recovers as is and everything is back to how they were before the shock.

- The system recovers but is worse off than before the shock.

- The system recovers and is better off than before the shock.

The last three scenarios all touch on recovery, but only the last one captures the essence of real resilience. In today’s context, disaster resilience is not only about surviving a disaster, but thriving in spite of it.

Building vs. Programming

In a way, these two concepts can be interchanged, especially in the context of disaster resilience. But there are subtle differences that are important to consider.

Building a system’s resilience to disasters means increasing or enhancing its overall ability to absorb, resist, adjust to, respond, and recover from the impact of disasters.

Programming a system’s resilience means setting up mechanisms (structures and processes) that will allow it to absorb, resist, adjust to, respond, and recover from disasters.

Simply put, resilience building is the end goal, resilience programming is the way to get there.

As Timothy Frankenberger explains it, “resilience building relies on integrated programming — a cross sectoral approach with a long-term commitment to improving the three critical capacities: absorptive, adaptive, and transformative” (Frankenberger, Constas, Nelson, & Starr, 2014)

Resilience Programming

Programming resilience into a system requires developing specific policies, programs, processes, capabilities, and resources that will contribute to its overall ability to bounce back better from a shock. These five items can also be the starting points in evaluating and subsequently developing the system’s resilience architecture.

- Does the system have an existing policy for managing risks and responding to shocks?

- Does the system have programs in place to ensure risks are managed well and adequately respond to disruptions?

- Does the system have processes in place for preventing/mitigating, preparing for, responding to, and recovering from any form of shock?

- Does the system have the internal capabilities to implement its programs and execute its processes?

- Does the system have the resources (finances, tools, equipment, people, etc.) to ensure its ability to bounce back better from shocks?

In the context of this article, a system is any functioning unit, group, organization, or institution e.g. an individual, a family, a company, an organization, a country.

The Resilience Programming Framework

The programming framework developed by Resilient.Ph is composed of five key elements or resilience drivers:

- Asset Protection and Risk Management (APRM)

- Enterprise (Business/Public Service) Continuity Planning (ECP)

- Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR)

- Crisis and Opportunity Management (COM)

- Resilience (Risk and Crisis) Communication (ResComms)

Each one has a specific objective and requires resources and competencies. Note that these elements are not entirely new concepts. They are already well-established measures used by systems. However, they are oftentimes thought of independently and in a linear way.

By integrating these elements into its core operation – ensuring that the necessary policies, programs, competencies, processes, and tools are available to effectively execute them, a system can build up its ability to bounce back better after any identified shock.

Asset Protection and Risk Management (APRM)

Protecting what you value most is the natural starting point of resilience programming. Of course, it goes without saying that one must first identify what this asset is. In today’s business discourse, this would generally include people, profit, and planet. Some would be more specific and list down people, product, business operations, information, finances, and tangible properties as key assets.

Ace And Associates Risk Management, Inc., an asset protection and risk management consulting firm, conducts holistic and independent risk exposure assessment as their first and crucial step in any protection program for their clients. They believe that while most organizations have already set-up a robust risk management system, others, specially government entities, have yet to recognize the critical need for a holistic risk exposure assessment as the foundation of all plans. Ace And Associates or AAA experienced revising a number of corporate security and safety management plans that were based on site security surveys and inspections, not from a risk and resiliency lens.

You cannot manage what you do not know. If a system is unfamiliar with the risks that its assets are exposed and vulnerable to, chances are, that system will not put in the necessary risk management measures, or, if it does, the measure may not actually amount to any form of protection at all.

Once the risks are clearly identified, the system can choose any of the following measures to manage them, depending on likelihood and impact.

- Accept

- Avoid

- Transfer

- Reduce

In many instances, risk reduction is the go-to approach. For example, to reduce the risk of employees getting infected with Covid-19 at work, social distancing is enforced within company premises and every employee is provided with adequate personal protective equipment and hygiene resources.

With a holistic and effective APRM, a system will have an easier time responding to any disruption or shock. The APRM is where the basic security and safety management are happening. No organization wants to have a security incident or accident to happen. The more robust and effective the APRM, the lesser probability to manage the consequences.

Continuity Management (CM)

Whether public or private, a system needs to deliver or provide the services or the goods that its end users expect from it. In order to ensure that these goods and services get to end users at the expected time, operations would have to be protected from any and all disruptions.

Without a properly done continuity plan, this would be hard to achieve, especially if the disruption is serous such as in the event of a major disaster. A properly done business continuity plan is not the shotgun approach of emergency or contingency plans which a large number of companies thought of BCPs.

Critical to an effective continuity plan is a properly mapped out and documented supply chain ecosystem. With a clear perspective on how every moving part in the supply chain operates, including their interdependencies with other supply chains, a system will be able to plot in contingency measures for any eventuality.

Some organizations designed their continuity plans solely on the need to secure their digital information systems. In reality, there are other aspects of the organization’s operations that get affected by shocks, including its people. If the continuity plan does not take into account the other aspects of operations, a system runs the risks of not being able to effectively manage disruptions.

In today’s VUCA world, BCPs should be enterprise-wide and consider the other resiliency modules other than the government’s public service continuity plans.

Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR)

APRM is about managing risks in general. DRR is specifically about disasters. A disaster is a situation where a system is severely impacted by a natural or man-made hazard that its resources are inadequate to meet the needs of its people and thus, requires assistance from outside sources.

Not every natural or man-made hazard that happens is a disaster. But all of them have the potential to become one depending on their severity and the vulnerability of the system.

Disasters usually impact multiple systems or communities. As such, disaster risk reduction must also involve all stakeholders at risk. One system or group cannot do it alone. Everyone must pitch in and help in reducing disaster risks.

In the RPF, the DRR acts as the conduit for co-ownership, co-creation, and collaboration to establish community disaster resilience. The synergies across stakeholders that allow for a co-created DRR strategy could also be tapped to respond to disasters and manage recoveries.

As a country that is constantly under the risk of disasters, we need to find a sustainable way to work together to reduce our exposure and build our resilience.

Opportunity and Crisis Management (OCM)

While most organizations would have implemented its crisis management programs, very few have taken the step further and considered the opportunities emerging from every crisis or disaster.

This element of the RPF focuses not only on the effective management of serious shocks and the reduction of its impact to the system but also on the potential for growth and innovation that comes with every shock.

However, when one looks at a crisis, disaster, or any shock, , one is bound to see any or all of the following:

- gaps in current policies, programs, capabilities, processes, and tools

- changes in public expectations

- changes in industry practices

- demand for innovation (new products and services)

If a system can identify these and subsequently come up with improvements to its operations, develop new approaches, or create new products and services, it would be in a stronger position than before the disruption or shock.

Resilience Communication (RC)

Communication cuts across all elements of the Resilience Programming Framework. But under resilience communications two specialized forms of communication are critical — risk and crisis communications.

Risk communication is a two-way process. It is supposed to allow the exchange of critical messages (information, warning, advice, etc.) from the experts or leaders to the stakeholder at risk and vice versa. It is supposed to be a continuous loop as systems are constantly at risk. The challenge is developing a risk communication strategy that manages information overload and communication fatigue.

Crisis communication is primarily for managing an ongoing severe shock or disruption to the system; hence, it directs specific stakeholders to act or behave in a specific manner that effectively reduces the impact and resolves the situation. Conveying the right message prevents the onset of another risk or crisis in a different dimension.

Resilience communication is the reframing of both risk and crisis communication in order to emphasize the higher goal of bouncing back better. As a continuing loop, both forms reinforce one another and direct the system to move towards resilience.

References

Building Your Resilience. (2012). Retrieved August 08, 2020, from https://www.apa.org/topics/resilience

Defining Resilience, Adaptive Capacity, and Vulnerability. (2018, January 11). Retrieved August 08, 2020, from https://serc.carleton.edu/integrate/teaching_materials/food_supply/student_materials/1059

Frankenberger, T. R., Constas, M. A., Nelson, S., & Starr, L. (2014). Resilience programming among nongovernmental organizations: Lessons for policymakers. Washington, DC: International Food Policy Research Institute.

Resilience. (n.d.). Retrieved August 08, 2020, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/resilience

UNISDR. (2009). 2009 UNISDR Terminology on Disaster Risk Reduction [PDF]. United Nations Office of Disaster Risk Reduction

About the Authors

Augustus Caesar Esmeralda (Ace) and Walter Panganiban (Wally) are the founders of Resilient.PH, where they currently serve as Chief Resilience Officer and Chief Communication Officer, respectively. Both are set to complete their Executive Master in Disaster Risk and Crisis Management (EMDRCM) Program at the Asian Institute of Management (AIM), where both are among the batch’s top students.

Ace is a former Army officer, a licensed insurance adviser, an entrepreneur, a farmer, a consultant, and a certified professional in several specialized courses beyond asset protection and risk management. He has a Master in Management degree also from the AIM.

Wally is a former seminarian from the Society of St. Paul, who has spent most of his career to date on corporate communication and public relations serving multinational companies in the FMCG sector. He pursued a Master in Communication Research from the University of the Philippines, Diliman.

Their shared passion and advocacy for helping communities bounce back better have brought them together to develop the resilience programming framework for Resilient.PH.